Paul Conroy: The Faces of War: A Glimpse Through Photojournalism @ TEDxLisboa

Journalism—the practice of reporting on events, people and facts—is a powerful method of storytelling. The (unbiased) goal is to tell us what happened, where it happened, who was involved, and what they said. When it’s done well, there’s an opportunity for us to see the world around us through a slightly different lens.

Journalists often develop their stories in a secondhand fashion with information from outside sources. But the most impactful reporting happens on site, inside the action as it’s taking place. Not only is there a story about the events, people, and facts, there’s a second story unfolding at the same time. It’s the journalist’s personal story. A narrative which reveals what’s happening to them, as well as what they’re thinking and feeling.

This is especially true for photojournalists who work in conflict zones. A soldier engaged in battle will have some degree of agency, but anyone with a camera instead of a weapon does not possess that advantage.

As a curator and advisor for TEDxLisboa 2023, I had the honor of working with award-winning photojournalist Paul Conroy on his talk. While most speakers I work with are sitting in a safe place—at their office or home—Paul was on the front lines in Ukraine, in a city that was being bombarded by Russian forces.

Whenever we spoke Paul’s face was lit only by the glow from his laptop screen.

“I can’t turn on any lights or the Russians will target the building I’m in.”

He took a short break from the front lines to give this talk, but he’s now back in Ukraine. His talk is not about the conflict he’s covering today—he’ll need to give that talk one day—but rather about his harrowing adventure while in Syria with Marie Colvin. Her passion for telling stories of warfare ended up costing her life. It was Paul’s honor to tell the world this story.

“So, once again, I’m back to shining lights in dark places, the haunts where despots and dictators like to operate. Once again, camera in hand, I’m back to peeling onions.

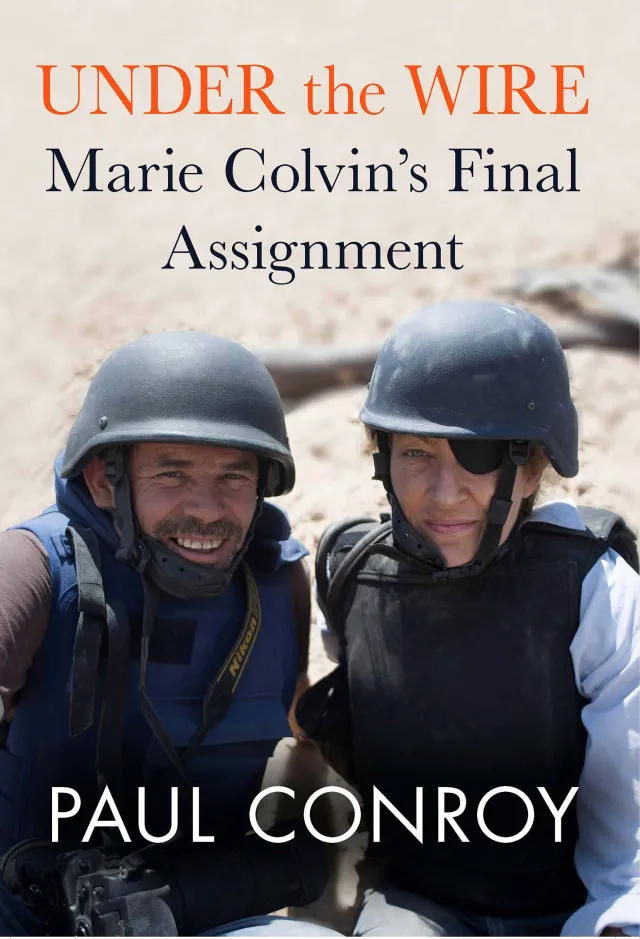

To get the full picture of Paul’s experience in Syria with Marie, I recommend reading his book, Under the Wire.

The full story would take many, many hours to tell, but Paul masterfully crafted a narrative that spans less than 20 minutes, yet takes you on a journey to hell and back. He choose to reveal the story in ten steps, and he calls out each one along the way. Unusual for a TEDx Talk, but I found it to be an effective way of pacing the story.

Transcript

One – Assignment

Home for me in 2012 was a 17th century cottage set in the Devon countryside. I’d been in Libya for a year covering the revolution with my dear colleague Marie Colvin of the Sunday Times. I’d met Marie in Syria in 2003 when we were both trying to break into Iraq illegally, and we’ve been best friends ever since then.

The piece of my Sunday afternoon was broken with a call from the Sunday Times picture desk. “Paul, we need you to go into Syria, meet Marie in Beirut,” said Andrew.

Trouble had been brewing in Syria since the start of the Arab Spring, but now Assad was shooting protesters in the streets. By midnight that night I was at Heathrow Airport, shoving 20,000 pounds down my boots, in my jacket. There was a limit of 10,000, and I just hadn’t read the paper.

So the next day I met up in Beirut with Marie and we started planning our trip into Homs. We knew the city was under siege. We’d been watching it streamed on the internet, and the journalists coming out were telling us it’s too much, it’s over for us. And Marie just laughed, shrugged her shoulders, and said, “It’s what we do.”

She’d once given a speech where she said we were there to bear witness, and she used the analogy that getting to the heart of any story was like peeling back the layers of an onion, and when you got to the core of the onion, that was the story, that was where you needed to be.

Two – Beirut, meeting the smugglers

We spent a few weeks in Beirut meeting up with representatives of the Free Syrian Army. They were the armed group opposing Assad, and they finally gave us a location and a time, and we had to meet up with a guy called ‘Beardy Man’, that was his name.

Two o’clock the next day in Starbucks we sat opposite Beardy Man and two other guys, and he has got a big beard, and he’s got his laptop out and he’s assessing us. By assessing, I mean he’s Googling us, reading Marie’s stories and looking at my pictures. And after a while he just leans back, gives a thumbs up, and goes, “You’re in.” We’d passed the Beardy Man test.

Three – The journey to the mountains

On a cold chilly morning in February the Free Syrian Army loaded us in to a rickety old van with other people, fare-paying passengers, and we began the drive north to Syria.

We were going in illegally. We had no visas. We’d both been banned from Syria years ago so it was hopeless. But our fixer, Lena, had been told by Lebanese intelligence in Beirut that any journalists found in the vicinity of Homs were to be executed, and their bodies were to be thrown onto the battlefield.

As we neared the mountains, a sense of doom kind of settled on both of us. We could hear explosions in the distance, and we knew too well that them explosions, the source of them explosions, were where we were headed, Syria.

Four – Crossing the border

We waited for hours in what was little more than a shepherd’s hut while the Free Syrian Army fed us big bowls of meat stew, which we sat there eating. Eventually at midnight they called us outside. “Stay close,” warned a shadowy figure, there are many soldiers.

So we spent the next hour tiptoeing through a deserted village, a minefield, around these army checkpoints, and all the time following the only visible sign of our guide, which was his white training shoes in the night. And as we skirted the army checkpoints, occasional shots rang out, but after an hour we were in Syria, we’d made it in.

Five – The road to Al Bueda

We travelled by car, van, motorbike, avoiding regime and Hezbollah checkpoints. It took about three days to travel 30 kilometers, as all the time the Syrian army hunted the press and the journalists with the same murderous intent. The regime were everywhere in Syria, there were no safe spaces.

Army vehicles patrolled the roads, and the checkpoints were random and often. Progress was painfully slow. We never undressed, we never took off our boots, and every night before we went to sleep we planned an escape route out into the olive groves.

Six – The tunnel from hell

In the middle of a cold wet field at midnight the FSA led us into a tunnel. It was actually a three foot high sewer drain, concrete, with no lights. There was very little air, and the heat build up was intense. The only way we could carry our kit was strapped to our chests, and because of the height of the tunnel we kind of had to walk bent double.

As we progressed down the tunnel we were passing people evacuating the wounded and the dying. This tunnel was a lifeline to Baba Amr, a small sunny neighborhood in Homs that was considered the beating heart of the revolution.

Everything came through this tunnel, some of it on the back of a motorcycle that burnt up precious oxygen for those on foot, and we carried on walking bent double for three miles. At the end of the tunnel they pulled us out into a warscape that was akin to one of Dante’s inner circles of hell.

As I looked around I could see the still smoldering skeletal remains of buildings, and it was all lit by the pale light of a full moon. We were driven at breakneck speed through a barrage of RPGs – that’s rocket propelled grenades – and heavy machine gun fire until we arrived drained and exhausted at the media centre.

The media centre was the source of all information coming out of Syria during the revolution. But the reality was, it was a three-story building. Inside there were twenty young Syrians, wrapped in blankets against the cold, all murmuring into Skype. The only light was the pale blue glow off their laptop screens.

Seven – The widow’s basement

While we were in Homs, we’d heard talk that there was a basement where all the women and the children who’d lost husbands and fathers were sheltered. It was one of the few shelters in Homs and it was known as The Widow’s Basement. The camera always affects people’s reactions when you pull one out, so I got Marie to go down first, and I sat at the top of the stairs with a long lens taking shots.

This picture captures exactly what Marie and I saw. This is the true face of the victims of war. This was our story. This was the core of the onion. Inside the basement one woman had given birth, but due to malnutrition she couldn’t breastfeed, so the baby was being fed on a mixture of sugar and water.

While Marie interviewed the tragic victims, I wandered round taking shots of the elderly, the children, and the dying. Wale our beloved translator, he heard of the death of one of his friends during one of Marie’s interviews, which was absolutely heartbreaking. But Marie shone. This is why we did what we did. These were the people who had the least control over their destiny in any war situation.

Eight – The field clinic

After the widow’s basement we ran to the field clinic. It was the run of death. Explosions ripped up the tarmac behind us as Assad’s gunners fired round after round of rocket and artillery fire. We arrived at the basement, ears ringing, nerves shredded, and they dragged us into the doorway.

We were greeted by Dr. Mohammed and a scene of absolute carnage. The dead and the dying filled up every gurney, every bed. The floor was awash with blood, and the medical staff dragged and stacked bodies anywhere they could find the space. They worked with first aid kits. There were no CT scanners or x-ray machines, just bandages and plasters of Paris. It was actually one of the worst places I’d been in any war zone.

Nine – Death and injury

On the 21st of February, both Marie and I agreed we weren’t going to get out alive, so we should do stories on BBC, CNN and Channel 4. Marie told the heartbreaking story of a young toddler who died of shrapnel wounds to the stomach, and the images went out to the world.

About midnight, not long after the interview, it was about midnight, there was a knock at the door, and I was like, “Who the hell is that?” We opened the door and there was three French journalists, Edith Bouvier, William Daniels and Remi Ochlik, and they’d just come in through the tunnel.

So the next morning, me and Marie woke up at 5am to go back to the field clinic. Before we left the building there were two almighty explosions, one 100 meters either side of the building and we waited 30 seconds, and then there were two more explosions, this time no more than 50 meters away.

I realized at that point in time what they were doing, they were bracketing, they were walking the shells in on the building. Thirty seconds later, the first shell hit the media centre. It destroyed the roof and the ceiling, and everything fell on top of us.

The second shell hit the back of the building where Marie and I had just been sleeping. That was destroyed. The third shell exploded somewhere in the building, and that filled the room with black acrid smoke and concrete dust. Seconds later, the fourth shell hit, killing Remi and Marie instantly.

I was still conscious, and I’d felt a pressure on my leg, so I leaned down to investigate, and as I touched my leg, my hand went through and came out the other side. And for a few moments I stood there wiggling my hand. I grabbed the artery inside to see if that was still intact. It was.

I grabbed the bone, that wasn’t broken, but I knew I had a few minutes to get a tourniquet on, otherwise I would bleed to death. So I grabbed the scarf from around my neck, wrapped it round, pulled it as tight as I could. But after a few minutes, I was still bleeding out.

I saw an ethernet cable in the rubble, so I grabbed that, wrapped that round, grabbed a piece of wood from the building, and pulled that as tight as I could. After about 20 minutes, the Free Syrian Army came, dragged me out of the rubble, and took me to the field clinic where Dr. Mohamed was stood there and he’s like, “Hello Paul, what’s wrong with you?”

And I’m going, “I’ve got a hole in my leg.” And he’s going, “Oh so you have.” So, Dr. Mohamed grabs a toothbrush and a bottle of iodine, and my leg is about that big, the hole, and he just pours iodine in with a toothbrush and spends 10 minutes scrubbing my leg.

And every time it nearly got clean, another shell had hit the building and concrete dust would fall in, so he’d have another go. And I was going, “Is that a toothbrush?” He’s going, “No, no, no, it’s a medical brush.” So eventually, he says, “We’ve run out of stitches.” And I was like, “Uh oh.” I said, “What are you going to use?”

He goes, “We’ve got this.” And he had an office staple gun. And I mean, he put about 40 staples into my leg, and there were no painkillers, so that was fun.

Ten – Born again

Myself, Edith, William, and Wale spent the next five days under heavy bombardment in an FSA safe house. It was the most intense artillery I’d ever known. Minute after minute, hour after hour, day after day, they just bombed and hit that building. After six days, the FSA came in and said, “Paul, everything is gone.”

The water tanks on the roof had been hit, the food supplies had run out. And they said, “Whatever happens, we will take you out tonight.” They piled us into five different pickups, and throwing all caution to the wind, we just drove straight at the front line.

The Assad’s forces responded with mortars, rockets, sniper fire, and machine gun fire. And believe me, that was the trip from hell, we managed to get through. Miraculously, we made it to the tunnel, and they tied a rope around my waist and dropped me into this hole, and then they put me on the motorbike that we’d used to ferry supplies. So I thought, great, getting a lift out.

So we’re on the motorbike, going down the tunnel, and we get about three-quarters of the way down, and the motorbike stops, and I look up, and the tunnel is blocked. I thought, oh dear God, no. We got a torch, and you could just see at the very top of the blockage, they’d carved a mini tunnel about the size of someone’s head and shoulders through the blockage, and I was like, uh-oh.

So they picked me off the motorbike, and they pushed me up towards this hole. And there’s no lights. This is all in the dark. The only way I could do it was to put my hands in like that, and pull myself through this blockage.

I got about two meters in and stopped dead. What had happened is a piece of the steel reinforcing bar had gone in my leg and out the other side. And so now I was pinned inside a tunnel, in a tunnel. And they’re going, “Hurry up.”, and I’m going, “Okay.”

So I’m like that, and I know what I’ve got to do in my head. I know I have to rip that wound wide open and actually make it bigger in order to get it off this metal bar. So I gritted my teeth, bit my tongue, and spent five minutes making the hole in my leg a lot bigger.

Eventually, I did that, and I crawled another meter or so through this tunnel, in a tunnel, and I fell out the other side into a pool of mud, and I could feel the water swilling through my leg. “Whatever I say guys, put me on a piece of plastic.” And together, they carried me out. And finally, I escaped the tunnel.

For the next five days, I traveled across Syria on the back of a motorbike. They put some plasters on my leg. I don’t know what it was, but my leg was essentially hanging off. Drove across the tunnel on the back of a motorbike across Syria.

Occasionally, we stopped at farms that were friendly to the cause, but, you know, we never actually got to sleep. And against all odds, I made it to Beirut, where the British ambassador, Tom Fletcher, and his family welcomed me into their home.

Two days later, the Sunday Times arranged a medical evacuation. And I remember really clearly, I was at Beirut airport, we’d sneaked in with the SAS, and I’m on my wheelchair like that, and the British military attache walks over, and he’s like, he leans in, salutes, and in the poshest British voice, he goes, “I believe things got a little fruity out there, sir.” He was the master of British understatements.

So, I wrote this speech and rehearsed this speech in Kherson on the Ukrainian front line as the Russians were pulverizing the city. In fact, this is the first time, or second time, I’ve read it through without an explosion, so well done, Portugal. But Kherson exists in a state of terror. Where once there were 300,000 people, there are now 10,000 people, and the Russians are dismantling the city.

Every day, people crushed by the horror of war leave on the buses going out. But this is how we gather a story. It’s a long shot from grabbing a shot on a cell phone and posting it on Instagram.

We live in dangerous times where misinformation can directly affect events on the ground, and the need for objective, impartial journalism has never been greater. I think photojournalism still has the power to affect outcomes in war.

Why else would I be there?

But for a story to have true impact, you have to report from the scene, and not from a safe distance. So, once again, I’m back to shining lights in dark places, the haunts where despots and dictators like to operate. Once again, camera in hand, I’m back to peeling onions.

Thank you.

◆

contact me to discuss your storytelling goals!

◆

Subscribe to our newsletter for the latest updates!

Copyright Storytelling with Impact – All rights reserved